When teams start a hardware project, the concern is often the same: once something physical exists, it feels difficult to change. Early decisions are assumed to be permanent, mistakes expensive, and progress hard to reverse.

In practice, the bigger risk is usually not moving too fast, but committing too early. Many teams try to make early work look final before they have enough information to justify it. That instinct is understandable, but it often creates the very rigidity people are trying to avoid.

Early-stage hardware work is not about getting things right. It is about learning what matters while changes are still cheap.

1. Decide What Must Be True for the Idea to Be Viable

Every hardware concept depends on a small number of assumptions. If one of them turns out to be wrong, everything built on top of it loses its value.

Typical examples include:

- whether a sensor produces data that is actually usable

- whether an interaction makes sense without explanation

- whether the system behaves acceptably outside a controlled lab setup

What causes trouble is trying to validate everything at once. That approach spreads effort thin and produces ambiguous results. In many projects, only one or two assumptions truly matter at the beginning.

In my experience, framing the prototype around those few assumptions changes its purpose. It is no longer a first version of a product, but a way to answer a specific and sometimes uncomfortable question early.

2. Learning Comes Before Polish

This is often where tension appears.

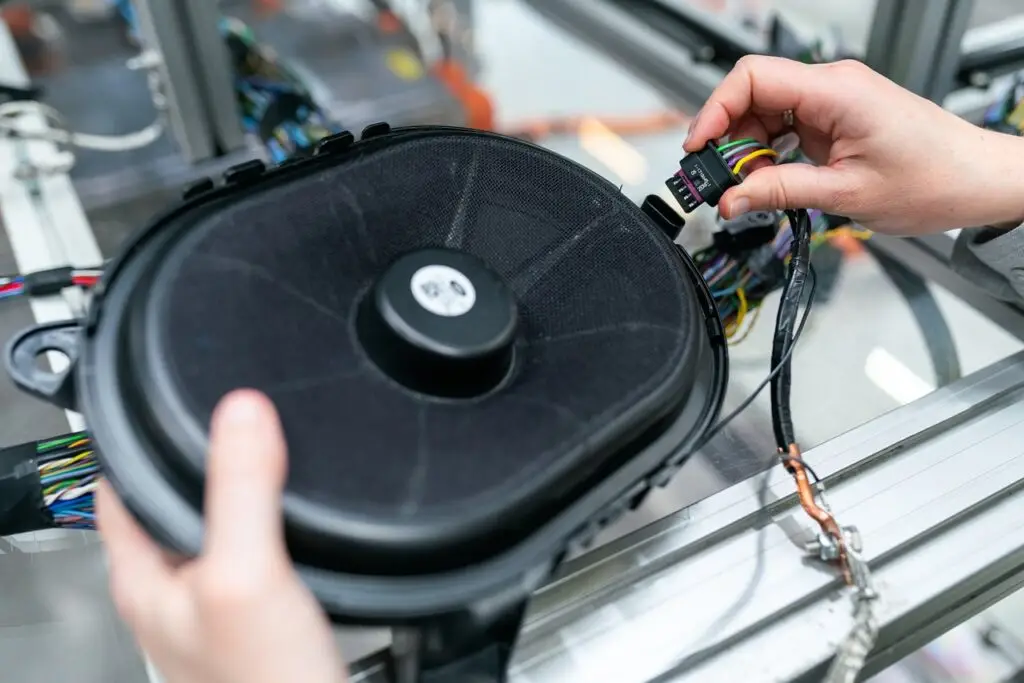

There is pressure to make early prototypes look credible. Clean integration, neat wiring, and refined enclosures feel reassuring. But polish can hide risk, especially when the underlying behavior is still uncertain.

Rough prototypes tend to expose problems sooner. Visible wires, off-the-shelf modules, and manual steps are not signs of carelessness. They are signs that learning is still the priority.

I have found it safer to build only what is required to observe real behavior. Everything that does not contribute to that observation can usually wait. It is much easier to add polish later than to undo early commitments made for the wrong reasons.

3. Keep Decisions Reversible as Long as Possible

Early progress in hardware depends heavily on feedback speed.

Using development boards, modular components, and existing subsystems helps shorten feedback loops and keeps options open. This is not about cutting corners. It is about delaying irreversible decisions until there is enough evidence to support them.

A prototype that can be modified next week is often more useful than one that looks finished today. In early stages, technical elegance and real progress rarely move in the same direction.

4. Make the Prototype Observable

A prototype is not just a technical artifact. It is also a communication tool.

Non-technical stakeholders do not need to understand how something is implemented. They need to see it turn on, react, and behave in a way that feels real. Once that happens, conversations change.

Questions become more concrete. Opinions calm down. Discussions move away from abstract risk and toward observable facts. Even a partial system can be enough, as long as it demonstrates real behavior.

This is often where confidence begins to build, not because everything is solved, but because uncertainty is no longer theoretical.

5. Treat Each Prototype as a Filter, Not a Milestone

Each iteration should narrow the decision space.

After a prototype has done its job, it should be clearer:

- what works well enough to keep

- what does not justify further investment

- what uncertainty deserves attention next

Progress is not defined by completeness. It is defined by clarity. When questions shift from “does this work at all?” to “how should this be improved?”, the project is usually ready for deeper technical commitment.

Skipping this filtering step often leads to more work later, not less.

Practical Takeaways

- A prototype succeeds if it answers an important question

- Early hardware risk usually comes from premature commitment, not imperfection

- Rough prototypes often reveal more than polished ones

- Physical demonstrations align people faster than documents

- Learning speed matters more than refinement at the beginning

Conclusion

Testing a hardware idea early does not mean locking in a design. It means choosing carefully what to prove first, and building only enough to prove it.

When teams focus on reducing uncertainty rather than chasing completeness, hardware development becomes more predictable and far less intimidating. Confidence grows not from having all the answers, but from knowing which questions have already been resolved and which ones remain.

That mindset is often what separates hardware projects that drift from those that move forward with intent.